The image of the body being pierced by fine needles in an apparently random way is perhaps the stereotypical view of Chinese medicine.

At face value, it must be difficult to imagine how this kind of treatment can benefit particular problems. For most people in the West, Chinese medicine will start and end with this image—somewhat arcane and bizarre, and something to be doubted or feared. But the Chinese have been using and refining the techniques of acupuncture for more than 3,000 years, with consistent and remarkable effect.

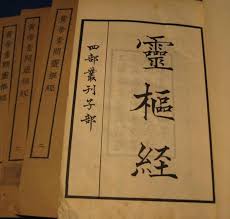

It should be remembered that acupuncture has evolved as an essentially empirical science—in other words, it is founded on a body of knowledge that has been developed from the on-going and systematic observation of the effect of needling specific points and areas of the body. Initially, crude needles, made from sharpened stones, animal bones, or bamboo, were used “to remove obstructions from the channels and regulate the flow of blood and qi.”

This quote, from some point between 200 B. C. and A. D.100, indicates that the theory of acupuncture has been in place for centuries. Over time, the initial practice of inserting “needles” into “ashi” points (where pain is experienced) was systematically developed: the energetic model of qi, jing, blood, and fluids was articulated, and the energy flows were mapped as the meridians of the body. Specific points were identified, and their actions recorded. Even now, the theory of acupuncture continues to be developed and refined.

In terms of clinical practice, acupuncture today is a far cry from the early developments, but fundamentally the theories and principles remain the same.

In Chinese medicine, a disharmony can result from a variety of factors, including

1. A deficiency or an excess of the yin and/or yang energy of the body

2. An invasion by an external pathogenic factor, which may remain superficially on the outside of the body or penetrate more deeply into the interior of the body

3. A problem at the level of the channels or the collaterals, or affecting the functioning of the internal zangfu system of the body

4. Heat or cold associated with the disharmony

The diagnosis of the patient’s disharmony in terms of the eight-principle patterns leads to an understanding of what the treatment seeks to achieve. Acupuncture works by addressing the identified treatment principles. Thus, for example, when a pattern of deficiency is identified, acupuncture is used to tonify the appropriate energy system of the body. Since Chinese medicine sees all illness as a process of energetic disharmony—which acupuncture can help to reestablish—there are no disorders for which this form of treatment is inappropriate.

There are very few situations where acupuncture is contraindicated. The following are the most common.

1. Where the patient has a hemophilic condition.

2. Where the patient is pregnant (certain points and needle manipulations are contraindicated in pregnancy)

3. Where the patient has a severe psychotic condition or has recently taken drugs or alcohol. Although acupuncture would generally be contraindicated in these circumstances, it should be stressed that it can be very helpful in drug and alcohol rehabilitation regimes.

There are no contraindications for the use of acupuncture in the treatment of patients with HIV-related disorders, although rigorous hygiene protocols must be adhered to. Given the energetic nature of most HIV-related disorders, acupuncture can be very helpful to patients suffering from AIDS since it can address a particular disharmony in a very specific manner—often more effectively than drugs. Acupuncture cannot offer a cure for AIDS, but it can be most helpful in supporting the management of a variety of symptoms connected to it.

There are some conditions –psoriasis and eczema, for example—where acupuncture may have limited success on its own, but for these it can be effective alongside other treatment, especially herbal remedies.

In the West, the problem for many practitioners of acupuncture is that most people they see have long-term chronic condition. For these patient’s acupuncture is very often a last resort, and in such situations progress is likely to be slow, with a large number of treatments being required. This, of course, is not always the case; sometimes acupuncture can produce rapid and dramatic results. Also, as Chinese medicine becomes more established in the West, a growing number of patients are choosing this as their first option for healthcare, and the range of condition being successfully treated with acupuncture is growing all the time.

The rule of thumb for patients considering acupuncture is to assume that it will be able to help their condition—whatever it is. Thereafter, provided they consult an appropriately trained and experienced practitioner, they will be able to discuss in detail what acupuncture can do for their specific problem.

Needles are the main tools for acupuncture. Early needles were developed from sharpened stones, bamboo, and animal bones; and over the centuries, techniques have been refined to produce very fine steel needles. Initially, needles were sterilized, and this practice remains the norm in China today, sterilization standards are now very exacting, and practitioner in the West must follow rigorous guidelines.

Needles are available in varying lengths and thickness. The choice of needle to be used is left to the clinical judgment of the practitioner but is usually governed by the point being needled and the effect the practitioner is seeking in terms of needle technique. The most commonly used needles are between half an inch and three inches in length. Longer needles may be used on occasion; for example, very long and extremely thin needles are sometimes used to follow the line of the meridians around the scalp, just underneath the skin.

Very sharp “pricking” needles are used to draw small quantities of blood from certain acupuncture points; for example, blood can be drawn from the point on the lung channel at the outside edge of the thumbnail in order to expel excess heat in the lung—a very effective treatment for a sore throat caused by an invasion by wind-cold that has turned to wind-heat.

The “plum blossom” needle consists of a small hammerhead on a flexible handle. Up to twelve small, sharp needles on the head are used to tap gently on the skin to stimulate the flow of qi and blood in the local area. This usually produces a redness of the skin and on occasion can cause superficial local bleeding. Such techniques are clinically indicated in a variety of different conditions, and the practitioner uses professional judgment as to the appropriateness of the technique after discussion with the patient.